Our family was—and still is—enthusiastic about fireworks. There was a time David even slipped in some illegal in North Carolina, the kind purchased across the border in his state of South Carolina. Every Fourth of July, we sat on our lawn in anticipation. David stood yards in front of us on the street and lit the torpedo buzz, the rockets, all the funny-sounding popping crackers. We cheered and clapped and buried our faces in ripe slices of watermelon.

July 4, 1996, Daniel was in the hospital having his monthly chemo injections. Our celebration of our nation’s birthday would have to be held inside Daniel’s hospital room. Daniel looked forward to watching the fireworks, hoping his hospital room window would provide a good view. But a nurse informed us there wouldn't be fireworks from Kenan Stadium that night; the reason was unclear.

Daniel bounced back from his disappointment when friends Sue, and her twelve-year-old daughter, Becca, entered the room with a watermelon and a knife. "We came to celebrate July Fourth with you!" said Sue in her vibrant Rochester, New York, accent.

Sue cut slices for each of us and served them on paper plates. Becca placed a plate on Daniel's tray table.

Daniel dipped his mouth into the fruit. With juice running down his cheeks and chin, he took another bite. He found a black seed and, facing Becca, spat the seed toward her and then, grinning, waited for her reaction.

She laughed; he filled his lungs and cheeks with air and let out another. It landed on his sheet. Our family comes from a long line of watermelon-seed-spitters. Mom had won contests, but it looked like Daniel needed some tips from her.

After the two left, Daniel said, "I think I've had enough watermelon." He lay on the bed, comically rubbing his tummy and grinning.

I looked at the half-consumed treat. It was too big to store in the fridge in the communal kitchen down the corridor. "Where can we put it?" Where did other patients keep their watermelons?

I'd read the thick binder about Daniel's medications and various procedures, but nowhere in any of the literature was there a section about proper protocol for taking care of leftover fruit.

"How about in the bathtub?" Daniel said.

What a great idea! "Why not?"

And so, we did just that.

[The above is an excerpt from the memoir, Life at Daniel's Place, by Alice J. Wisler. Get the book here.]

Showing posts with label Childhood cancer. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Childhood cancer. Show all posts

Wednesday, September 13, 2023

Saturday, July 6, 2019

This is How You Eat Watermelon

This is how you eat watermelon.

Fully committed, no regrets, all in.

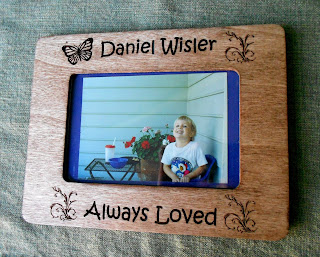

Daniel was three and had just been diagnosed with neuroblastoma, a malignant tumor in the left side of his neck. He'd had surgeries and a double-lumen catheter surgically-implanted in his body. His hair was going to come out, hence, the bowl-hair-cut, just to tidy it up until the inevitable happened.

Eight months later, he would die. His fun-loving and intelligent brain would suffer due to not enough oxygen. An infection was the culprit. That was the beginning of the end. The cancer wouldn't kill him; the treatments to get rid of it would.

But on this day in early June 1996, Daniel was happy. He was discharged from the hospital and there was watermelon waiting at home. He and his big sister sat on the driveway with their slices. Rachel picked hers up and took small bites. But not Daniel. He planted his face into his slice. Juice dripping down his chin, his cheeks, his neck.

Because that is who Daniel was. Full-throttle, energetic, silly, fun, not afraid to try something new. Enjoying our laughter.

In the twenty-two years since he has been gone, I've become extra fond of watermelon. Each time it is served to me, I feel I'm being honored with the memories of a precious kid. I want to remember; I want to dive into those special times he brought to our lives.

I miss you, Daniel. Thanks for showing me how to plunge in---even into the unknown---and not be afraid.

Friday, May 24, 2019

Grief Dates

"Grief is like the ocean; it comes on waves ebbing and flowing.

Sometimes the water is calm, and sometimes it is overwhelming. All we

can do is learn to swim."

~Vicki Harrison

Not sure why I was feeling sad on this Friday. I went through the usual check list.

Kids?

They are okay as far as I know.

Parents? Getting older, but healthy.

Friends?

Finances?

My health?

Carl?

It all showed up good.

I carried on, packing orders for our in-home business. Carl and I talked about Memorial Day weekend plans. I worked on a newsletter, did laundry, texted my kids, What was wrong with me? I felt as through I could burst into a puddle of tears. I made a cup of hot tea. Tea is soothing.

By 3 PM when Carl and I went on our daily trek to the local post office to mail orders, I was still unsure what was making me sad.

And then, as we sat in Friday Memorial Day weekend traffic, I realized today is the 24th, Could it be . . .?

With the help of Google, I found out.

"Google," I said into Carl's phone (I'd left mine at home), "What day of the week was May 24, 1996?"

And Google said, "It was a Friday."

And then all mysteries were solved.

Today is Friday, May 24th. Twenty-three years ago May 24th was also a Friday. Twenty-three years ago our pediatrician called to tell me that my three-year-old had cancer. Daniel spent that night in the hospital with his daddy as tests were done. Shortly after that, his week of chemo started. And nothing let up, no breaks, no good news, and then he died.

Obviously, I haven't sealed this date in my mind by remembering it; I've always associated his diagnosis with the Friday of Memorial Day weekend. Since every year the 24th of May doesn't fall on on a Friday, I just recall a little or a lot of that particular weekend. Some years I remembered how the hospital staff decorated his hospital room with Barney because Daniel had on a Barney T-shirt. They didn't know that Daniel only wore the shirt because I'd gotten it on sale at a consignment store. Other years what jumped out was that vivid scene of seeing another family headed in their van to a church picnic while our family was headed in our van back to the hospital.

The thing for me is the realization that even after all this time, Memorial Day still makes me sad. I can't hide it. You would think that time would take away sadness. It has reduced some of the intense heartache. But the sadness this day holds never fades. This was when I heard that my son had neuroblastoma. This was when I realized how one moment can change the course of a life and there is no going back to how things used to be.

We learn to swim in the waves of grief. We discover how to adapt to our new lives. I think we spend the rest of our lives navigating grief. It really is learn to navigate or sink. There isn't any other choice.

Memorial Day Weekend is a time to remember those we have lost over the years. I know the holiday was created to honor our servicemen and servicewomen, and I do that. But I also honor the memory and life of Daniel. He fought hard through every treatment. He was A Brave Cookie.

~*~*~*~*

Do you have certain dates that are sad for you because of the diagnosis or death of a loved one?

How do you handle the emotions? Does grief ever surprise you?

Labels:

Alice J. Wisler,

Childhood cancer,

children,

Daniel Paul Wisler,

grief,

Memorial Day,

neuroblastoma

Thursday, May 9, 2019

The Hand of a Preschooler: Mother's Day Reflection

It happens; things are moved, hidden items appear. I think that's some sort of law of nature. If it's moving a dresser to fit another piece of furniture into the room, what appears might be as nondescript as a couple of dust bunnies. You haul out the vacuum cleaner and let the evacuation begin. Run the Hoover over the spot and a dust-free carpet emerges. But if it's a tender memory that has been hiding, well, then, you bring out the tissues.

When Carl and I got a new king mattress and bed, we had to move the highboy dresser to make room. I expected dust. Dust and I are old pals, and I think she really likes me because I let her hang around, sometimes for weeks.

But it was what I didn't expect that got me emotional. There, along with the dust behind the dresser, was a Mother's Day card. Not only was it brittle with a rip in it, but it was from my son Daniel who died in 1997.

Wow.

On the light blue faded paper were his hand prints, a glitter heart, a heart in marker, and a few other squiggly lines, the kind preschoolers draw that hold hidden meaning no one else knows about. His teacher must have written the words for him: Happy Mother's Day, Love, Daniel. I wondered when this was created, perhaps something he had done in Sunday school the Mother's Day he was three. His last Mother's Day to give me a gift.

These are the kinds of things that you are relieved to find: Lost keys, eye glasses, a check for a nice sum of money. Finding a card from a child who has been gone from you for over twenty years falls into a whole different category. You aren't relieved because it wasn't lost. You are grateful. And a feeling of sacredness falls over you. The discovery of something he created is a sacred love letter that shouts out again and again: He lived! And he loved.

I suppose I placed the Mother's Day card behind the dresser when I first moved to the house. Probably with the intention to do something with it. Most likely thinking I'd find a real place for it. One day. And one day turned into fifteen years because you know, out of sight, out of mind.

I ran a finger over the two hand prints on the card. Right-handed prints. Daniel was left-handed. But in the hospital it was his right hand that I held that night he was having trouble getting to sleep.

"Mommy, where's your hand?"

I was in the chair bed next to his hospital bed. And he reached over the railing of his bed for my hand, I gave him mine. Holding hands against a cold hard railing got uncomfortable. When I thought he was asleep, I pried my fingers from his.

He wasn't asleep. "Mommy!" His tone was accusatory. "Mommy, where's your hand?!"

"Here it is." I put my hand out for him to grab.

And he did, clinging to it until, at last, he fell asleep.

That right hand was the same hand I held when we walked across the mile-high bridge at Grandfather Mountain. He was three, nine months before he was diagnosed with cancer. The bridge swayed in the wind. Daniel held tightly to my hand, not because he was afraid, but because I was. We walked together all the way to the other side. I wasn't sure I would make it. Frightened by heights and feeling paralyzed, I thought I'd wind up as the only person to need a helicopter to pull me off the bridge. When Daniel and I got to the safety of the other side and off the bridge, I almost kissed the ground.

This Mother's Day I'm grateful for memories and soft tissues. I've found over the years that emotions are never far, and sometimes they still surprise.

Happy Mother's Day to all the bereaved mamas out there who'd covet and treasure one last time to hold the hand of a son or daughter. May you find those gentle memories. Hold them close and remember.

And Daniel, thanks for the love.

Labels:

a mother's grief,

bereaved parents,

cancer patient,

Childhood cancer,

Daniel Paul Wisler,

Grief and Mother's Day,

Mother's Day gifts

Monday, August 21, 2017

Watermelon, Irises, Tomatoes, Geraniums, and a Spider: Does Time Heal Wounds?

In bereavement meetings parents have certain topics that continue to be discussed. One's about time and wounds. A mother who had lost her daughter to a car accident just weeks before my son died, said to the group, "They say that time heals all wounds." She was southern and I couldn't understand if she was saying "all wounds" or "old wounds".

I suppose the question that I wanted to ask was: Does time heal? At all? As the minutes, hours, and days tick away in agony, do all wounds get taken care of, soothed, do the scabs heal, do the ugly scars fade?

As a newly-grieving mom, I knew so little about the journey I had been forced to take, but I did know one thing, and that was that old scars do not fade away. I've had a scar since I was two, a paintbrush I was playing with in the bathtub attacked me and cut the skin near my left eye. My parents wrapped me in a towel, held me while I cried, felt awful, and later would wonder if they should have taken me to get stitches. The blood dried up, and healing started, but that scar is still visible all these years later.

So time doesn't heal old wounds. I suspect that after 54 years, that scar on the corner of my eye has done all the healing it is going to do.

No wonder I resonated with another bereaved mother, a veteran, who at fifteen years since her son took his own life, said to me over lunch one afternoon years ago, "I think I've done all the healing that I'm going to do."

She wasn't giving up on healing or digging a hole and hiding, she was being realistic. There comes a point in the bereaved parent's life when she or he knows that it is not going to get any better than this.

For me, I'm not going to be able to look at the things that remind me of Daniel and not feel that tenderness in my heart. Since his death, two fruits, two flowers, and one spider have kept me in the loop of significant memories. The watermelon, the geranium, the tomato, the iris, and the spider are some of the things that hold powerful remembrances for me. And depending on the time of year (Christmas, Daniel's birthdate in August or death date in February), if I encounter any of these, well, bring on the Puffs.

Society may think time washes it all away like an ocean wave. Build a sand castle at the beach and once the waves knock it down, there is no evidence that a sandcastle once stood in the spot. Many can't believe that after ten, fifteen, or twenty years a mother or father can still feel pain.

But it's not that our desire is to feel pain, it's that we want to remember and since our child is dead, of course, it's always going to make us sad.

When I see a purple iris blooming in my garden, I recall the time Daniel, at age three, couldn't say my name Alice well enough to be understood by strangers and they thought he was saying, "My mommy's name is Iris."

Daniel picked green tomatoes from our garden, even though I told him to wait till they ripened. He took a green tomato to the hospital once and put it on the window sill of his room. He had seen me place green tomatoes on the kitchen window sill at our home, with the hope that the sun would stream in and turn them red.

There are many watermelon stories, including the one where friends brought a watermelon to Daniel when he was in the hospital for chemo treatments on the Fourth of July. He ate a few slices, spit seeds (this was back when all watermelon had "spittable" black seeds), and then said, "I think I've had enough watermelon," and stored the leftovers in the bathtub.

One afternoon I heard Daniel chanting, "A spider, a spider for a pet, a spider for a pet," and when I found him, he was outside watching a tiny spider creep along the side of our house.

And then the geraniums. I would have forgotten about these flowers (and that apparently I was once able to keep flowers alive) if it weren't for the photo of Daniel seated in his blue plastic chair in front of a table with a cup of juice and a blue bowl of food. He chose to eat his lunch outside beside the potted red, pink, and white geraniums. He would have preferred to be naked if I didn't make him wear clothes. When I took that photo, I had no idea that the neck he exposed so nicely held a malignant tumor, one that would surface months later, and change his life and ours forever.

So does time heal old wounds, or even all of them?

No, and for me, that's a good thing.

[Daniel Paul Wisler, August 25, 1992---February 2, 1997]

Thursday, February 16, 2017

Twenty Years of Keeping On

When Daniel died in 1997, my pain was bigger than God. People would tell me that with time it would ease, or that they knew how I felt because they had a cat die and how awful that was.

"Just think," she said as I clutched the receiver, "God needed another flower in his garden and he picked Daniel."

After a few days, when the phone rang and her voice came on the answering machine, I didn’t pick up.

I washed dishes, fed Benjamin apples and bananas, read him stories, and when he was watching Sesame Street, I'd sneak upstairs into Daniel’s room. I’d breathe in the familiar smells it had accumulated: hospital soap, bandages, iodine. But the strongest scent of all was my hollow loneliness. It grabbed me in the gut and pulled me to the floor. Often I would let myself cry.

And that woman would keep calling to offer her words.

But I didn’t return her calls. I felt that since my pain was so large and consuming and I was six months pregnant that she would understand that I didn’t have the energy to call her back.

Eventually she stopped calling me.

And I became grateful for answering machines because they were like secretaries, weeding out the calls I was unable to take. Sometimes friends would call and I would stand by the phone and not answer. I let their voices be recorded and that made me feel that I had some control of my vacant life. I had a choice—to answer or not to answer. I grew more fond of the not to answer.

There were times I thought I was ready for Butner, the psychiatric facility off of I-85. I could walk outside and almost smell the sheets.

I went to support group meetings with other people who would just break into tears, unable to finish sentences, people with ragged photos of their children that they shared so that the rest of us could say, "She is beautiful," even though the child had ears that protruded and was cross-eyed and her dress was too short or too long or too pink. It didn’t matter because eventually I knew I belonged with these people.

I belonged to these parents, who introduced me to words I had never been allowed to say. Angry adults who taught me you can say damn, shit and hell in the same sentence and not be struck down or turned into a pillar of salt. We sat around tables that were much too small to hold our grief and took turns saying our dead child’s name.

I belonged to these parents, who introduced me to words I had never been allowed to say. Angry adults who taught me you can say damn, shit and hell in the same sentence and not be struck down or turned into a pillar of salt. We sat around tables that were much too small to hold our grief and took turns saying our dead child’s name.

I seemed to go on and on with all the medical procedures about how Daniel had been diagnosed with a malignant tumor in his neck and how he’d been through chemo and surgeries and radiation and how a staph infection entered his body. I had had little medical jargon in my vocabulary prior to his diagnosis and death and at these meetings I was using all I had learned. I had no idea how long or short my turn was supposed to be I just knew that I had to tell my story. I had to get it out.

Part of me hoped that as I talked, one of the bereaved parents would stop me and see that I had talked my way out of this horrible story and say, "Oh, no, he couldn’t have died from that, that isn’t medically possible. Go home, your son is surely still alive. Go home now."

And I’d leave the claustrophobic church basement and drive the 40 minutes down Glenwood Avenue to my home and sure enough, there Daniel would be sitting in front of TV watching The Three Stooges with David. And I’d be so excited and happy that I wouldn’t complain that it was 10 o’clock and that David should have already put Daniel to bed.

But even though I attended those meetings twice a month for two years, Daniel never came back. No loop hole in his death was discovered. And pretty soon my heart knew what my head did, my son was gone from this earth and I was going to have to live the rest of my life without ever holding his hand again.

I would write poems at the graveside and lift balloons into the air. I'd cry with other parents, speak at conferences, and raise my three other children and never know why Daniel didn’t get to be a hero and pull through the whole ordeal.

And I was going to have to adapt and adjust just like countless parents before me and just like thousands of parents would have to learn to do after me.

I was in this club that no one wanted to be part of, a club with rituals that no one understood except for the people in it, and a club that had no membership expiration date. Until you die. I would be thirty-seven, thirty-eight, forty, fifty, fifty-nine, gray, old, still showing dampened photos of a little boy who never grew up.

Sometimes when I’d be driving to the meetings, I’d think, what if I just rammed into the Mayflower truck in the lane ahead of me or just gunned the engine and took a leap off a cliff and died. What if . . . ? But then I knew I couldn’t do that to my kids, especially not to the baby because she was brand new and Daniel had told me when she was still in the womb the size of a raisin, and then even larger than that, giving me heartburn and kicking, that I was to take care of her.

So I’d follow the speed limit and take my eyes away from the Mayflower truck and keep going on.

For twenty years I've been keeping on. Truth be told, it is either to keep going on or to roll up and die.

I choose life. And I'm glad I did, and glad I do.

"Will I ever want to laugh again?" a young newly-bereaved mom asked me at a conference where I gave a writing workshop.

"Yes," I replied. "You will be able to laugh again. Trust me. And keep on. You can do it. Where there is breath, this is hope."

"My friends don't understand," she said as she blew her nose into a tissue. "One calls me every week to tell me to get on with life."

"Do you have an answering machine?" I asked and then realized that we are in the twenty-first century. Quickly, I said," You don't have to answer your cell phone every time it rings, you know."

She nodded. "I think I can do that."

But she's doubtful, I can tell by the hollowness in her eyes. I tell her I was there once, just as she is. Wondering, aching, unsure if I wanted to live or ram into the Mayflower truck.

She hugs me and we wipe our eyes.

I think she'll make it.

Many of us have.

For twenty years I've been keeping on. Truth be told, it is either to keep going on or to roll up and die.

I choose life. And I'm glad I did, and glad I do.

"Will I ever want to laugh again?" a young newly-bereaved mom asked me at a conference where I gave a writing workshop.

"Yes," I replied. "You will be able to laugh again. Trust me. And keep on. You can do it. Where there is breath, this is hope."

"My friends don't understand," she said as she blew her nose into a tissue. "One calls me every week to tell me to get on with life."

"Do you have an answering machine?" I asked and then realized that we are in the twenty-first century. Quickly, I said," You don't have to answer your cell phone every time it rings, you know."

She nodded. "I think I can do that."

But she's doubtful, I can tell by the hollowness in her eyes. I tell her I was there once, just as she is. Wondering, aching, unsure if I wanted to live or ram into the Mayflower truck.

She hugs me and we wipe our eyes.

I think she'll make it.

Many of us have.

Labels:

bereaved parents,

Bereaved Parents/USA,

bereavement,

Childhood cancer,

death of child,

remembrances,

The Compassionate Friends

Wednesday, September 2, 2015

Fellow Grievers, be that advocate!

When an appendage is removed from a person, a lot of adjusting has to take place. After the surgery and sutures heal, sometimes physical therapy is needed. The patient has to learn to adapt without a finger or arm or leg. Eventually, a new lifestyle is mastered.

As parents with children removed from us through death, we have to learn a new lifestyle, too. We adapt. We adjust. We cope. But some days we cry and wonder why the world seems to want to shut us out.

There is no way that a parent who has not lost a child to death will ever understand the pain, the agony of absence, and the multitude of emotions that are attached to living without a son or daughter. It's just impossible. I've never lost a limb (in the real physical sense) and I would never pretend to understand my friend Stella, who lost both legs when she was hit by a car.

Yet other parents feel the need to act like they get our pain. They sit with their healthy children surrounding them and tell us not to be so sad. "It'll get better." "You'll be okay." "He's in a better place."

You want to fight back and tell these parents that they don't get it. But instead of trying to get them to understand your grief, there are more dynamic ways you can choose to spend your time. Educate. Be an adcocate. Teach others in a way that they might be able to comprehend. Share with them how they can help you to make the world a better place.

Did your child die from an overdose? What leads to a life where one might die in this manner? What misconceptions do people have about teens and drug usage? Become an advocate for better awareness in this arena.

My son Daniel died from cancer treatments at age four. September is National Childhood Cancer Awareness Month, a month when I reach out via social media to let others know that kids can get malignant tumors. Kids can be born with cancer from no fault of their own or from their parents'. And yes, little children do die from cancer. Parents are empathetic in helping me get the word out because they realize that cancer shows no mercy to age, color of skin, or socio-economic ranks. If they are realistic, they know that any child can get cancer, just as any child is capable of dying from any disease or sudden accident.

I''ve written articles for magazines and newspapers about what striving for a cure means to me as a mom whose three-year-old was diagnosed with neuroblastoma, and what it means to thousands of parents across the country. I wear the gold ribbon as a visual to show my desire to fight for better clinical trials and for a cure for childhood cancer. And I think of my sweet bald-headed Daniel who called himself a Brave Cookie.

Find your place of passion and let others know about it. Use your energy, be fueled by it, even if it stems initially from angst at others' ignorance. Be that advocate in your child's memory! Let your lifestyle be one that encompasses the need for change.

Labels:

advocacy,

Alice J. Wisler,

bereaved parents,

cancer death,

Childhood cancer,

grief and loss,

loss of child,

National Childhood Cancer Awareness Month

Monday, August 24, 2015

One Tough Mama

"You are Wonder Woman. You know that, don't you?" The nurse in the recovery room kept her eyes on a drowsy Daniel but I knew that she was addressing me.

Me, the mom with an eleven-month-old son in a stroller, a child of unknown gender in my belly, and four-year-old Daniel in the hospital bed, about to wake up from his third radiation treatment.

I only smiled.

"One tough mama," she said. "You are amazing."

My daughter would have smiled at me had she been in the room, but she was in first grade learning to write about her brother Daniel. He and I like to red funny books. He has a boo-boo in his neck.

Daniel opened his eyes and looked around the room. "I had a nice nap," he said.

The nurse and I laughed.

This scene is only a memory now, a memory I have recalled over the eighteen years.

Eighteen years ago I did not think that I was a wonder woman. I was merely doing what any mom with a kid with cancer would do----one foot in front of the other, moving forward. It was a season of getting my three kids to where they needed to be when they needed to be there. For Daniel that meant getting him to radiation treatments every day at 6 AM for three weeks, and to the hospital once a month for week-long cancer treatments.

Tears? No. Sentiment? Who had time for that? I was one tough mama.

Eighteen years ago I was thirty-six, and believed that if you prayed hard enough and dreamed big enough, you would never have to live a life of heartache.

When Daniel died at age four, people told me that they didn't know how I did it. They used words like brave and strong and inspiring.

But now I wonder if they would understand that eighteen years since my little boy's body could no longer fight the battle, I'm a crumbling mess. I cry because at The Home Depot a tool set has been reduced to 1992, the year Daniel was born. There's a car in the parking lot with Dan on the license plate.

Days before my Daniel's birthday (he would be 23 August 25th), I am reduced to an ache so large that I wonder if the years have stitched up my wound at all. I recall his death and his birth and the four tiny years between the two events as I prepare dinner for the living.

My kids don't mind tears in the sauce. But they also know that I won't become sad when they head off to college or leave home for a dingy house with a group of boys before completing high school. They know I value the "normal" things kids get to do as they grow older and find their paths. I cherish them and that they get to grow up, fall down, get up, and try again. (And am grateful that the middle child did graduate eventually.)

This is who I am, this is the life of one tough mama.

Labels:

a mother's grief,

Alice J. Wisler,

bereaved parents,

Childhood cancer,

grief and birthdays,

grief and loss

Saturday, May 24, 2014

The Battle We Lost

It can make you feel that you're sinking or suffocating, or going through a little of both.

Eighteen years have passed and you'd think the damage would be over. Battle complete. Troops moved out. Rebuild. On to business as usual.

If only we were made that way.

As the holiday weekend approaches, I watch the men and women in uniform being honored, the waving Red, White, and Blue, read the grocery store specials on ground beef and chips, and feel this overwhelming ache. There stands what only I can fully see---a little boy in a Barney T-shirt and a pair of shorts. The boy needs a hair cut. His Mama wishes she'd taken care of that.

But in one second, a hair cut is forgotten. Because the boy needs so much more. He needs immediate surgery, a Broviac catheter inserted into his back running to his heart for chemo. Later he will need radiation. And stronger chemo. And prayers.

After the first week of chemo, hair falls out in clumps, sprawled out on the back seat of the dusty green van. A hair cut is not needed. His five-year-old sister cries when she sees his blond strands and balding head. "It's so sad," she whispers. We buy him a red ball cap to wear, one with dinosaurs. We buy him a blue one, too. He wears them for a few days, but when his head is smooth and shiny, he goes cap-less.

I recall how friends from church were driving in their van and passed us. I saw their smiles and knew that they were on their way to the Memorial Day church picnic. They turned right; we veered left toward the hospital. That image remains.

Every year for me, Memorial Day marks the beginning of the end. Eighteen years later and it feels just like yesterday when I sat on the sofa the Friday of Memorial Day weekend in 1996. The cordless phone was in my hand. The pediatrician told me that my son had a malignant tumor in his neck. The war raged from that day on, and on February 2, 1997, it ceased. All the surgeries, the chemo, the fight, the hope, the prayers-----over.

There was no victory; we lost.

Every year on Memorial Day weekend I am reminded of how much we lost.

Pushing it aside does no good. I have to acknowledge my heartache-----own it, for it is mine.

That's how we mamas are made.

And so I write on my blog and for some reason, that helps. Writing unleashes some of the ache so I can go to the picnics, hear the bands play, watch the fireworks. Writing keeps me from shattering like a bullet fired in the dark night.

For me, Memorial Day honors all of our soldiers---those here and those here only in the delicate arms of memory.

Labels:

Alice Wisler,

cancer,

Childhood cancer,

Daniel Wisler,

Memorial Day,

neuroblastoma,

tumor

Saturday, August 24, 2013

He was just a little boy . . .

It's that time of year again. That time when the yellow raincoat hanging in my closet feels as heavy as my heart. Everyone else is older now and with each passing year, this raincoat looks smaller than it did when he wore it. How could he have once been so small?

I look into the face of my son, that cute photo I took when I was just taking another picture of a child. Back before I realized that it would one day help to heal my heart.

There is so much I don't know. I don't know why Daniel spoke of Heaven so fondly. We never told him that he was going to die. I suppose it was because I never believed he would. Not until the very end after the staph infection shut his body down and the EEG confirmed what I did not want to hear. My son was brain dead.

Prior to that he looked into the sky one day and shouted, "I wanna go to Heaven!" His father and I looked at each other, speechless. No, no, our expressions conveyed. Not yet. Get well first and live and then die an old man.

I don't know why he wasn't able to die an old man. I don't know why he didn't even get to learn how to read.

He memorized. He memorized a complete book of jokes. And Maurice Sendak's Nutshell Library collection. "I told you once, I told you twice, all seasons of the year are nice for eating chicken soup with rice." He laughed at Pierre who got eaten by the lion and said, "I don't care." He loved for people to read to him. Curious George Rides a Bike. Are You My Mother? Where the Wild Things Are.

He spat watermelon seeds, built towers with Legos, loved Cocoa Puffs, and gave stickers to the doctors and nurses. "Because," he said, "you give presents to your friends."

After the doctors said there was no more that they could do, I kissed his cheek and whispered to him that he could die. "People tell me to let you go. To let you go. To say good-bye. You can go." The words sounded too harsh; no mother should have to tell her child that he is allowed to die. Quickly, I added, "But not yet. Not yet."

A bald-headed boy in a comatose condition, bloating on a sterile bed was better than no boy.

Each morning when I woke from the bed by his, I was relieved that he was still with us. Today was not the day I would have to deal with death. Not today. Not yet. I talked to him, I told him that I loved him. I told him he could die and I told him not to.

My mother was reading to him from a children's book about a boy who took a star from the sky and tried to keep it in his bed. But the star didn't belong in his bed and began to lose its light. At last, realizing that the star needed to be in the sky once again, the boy let the star sail back up to the heavens. "You can go, too," my mother whispered to Daniel.

Minutes later, our Daniel star left us. After only four years, his body had served its purpose. It was no longer needed. His spirit freely flew, sailing up to Heaven.

No more cancer, no more tears! "There are no tears in Heaven," he'd told me one day. Then he turned and asked me why.

"Jesus is there and there is no sadness when you are face to face with Him," I said.

There are no tears in Heaven, but there are plenty on earth. Especially when I hear Elton John sing Daniel or when somebody mentions Buzz Lightyear from Toy Story. Or when it's just an ordinary Sunday and the choir sings Amazing Grace.

I never thought he'd die. I always clung to healing, to health, to growing up with him, not without him. To more walks in the rain with him in his raincoat. To more times of him running out to greet the ice cream truck with all the change he could gather from the kitchen drawer.

I expected more birthdays, more kisses, more laughter. I wanted to send him off to kindergarten; instead I send kisses to Heaven. I take pictures of sunsets and sunrises, oceans and flowers, plant memorial gardens, and search for butterflies and rainbows. And I see the gap he has left between his older sister Rachel and his younger brother Ben and his sister Liz----the one he never met.

But after Daniel died, I remembered that I'd had a dream about six months into his treatment. He was climbing a ladder and the top of it was shaded by clouds. He was smiling, happy, no tears, no pain. He waved at me and continued to eagerly climb with a surge of energy. The next morning I shared the dream with my mom and my friend; their faces were sullen. What was wrong with them? My dream was a clear indication that Daniel was going to go from being ill to being free. His smile was a sure sign that he was going to be healed from the disease. We would have more of life here together.

Now I know that the dream was showing me that Daniel was climbing up to those clouds and beyond---beyond what I have ever experienced----where those who aren't around us anymore to share jokes live. I had wanted to keep him, hold onto him, I wasn't ready to let my precious star go back to where he came from.

I still want him here. With us. But I imagine Heaven is too wonderful to leave and once you are there, you are the happiest----your most perfect and content self----the way you were meant to be.

I love you, Daniel. I miss your bright blue eyes.

But your star shines bright. Especially tonight on your 21st birthday.

In memory of Daniel Paul Wisler: August 25, 1992 ~ February 2, 1997

Labels:

Alice J. Wisler,

bereaved parents,

birthdays,

cancer,

Childhood cancer,

Daniel Paul Wisler,

grief,

grief and birthdays,

loss,

loss of child

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

A Cup of Coffee

October, for me, will always be radiation month. My son Daniel was diagnosed with cancer in May, and by the fall, he was scheduled for radiation treatments every morning. For two weeks, after putting my six-year-old daughter on the school bus, my sons and I would make the trek to UNC-Hospital. After unbuckling both four-year-old Daniel and eleven-month-old Benjamin from their car seats, I would put Benjamin in a stroller. The three of us would enter the clinic. As we sat in the lobby, waiting for Daniel's turn for the tumor on his neck to be radiated, coffee in a Styrofoam cup, would be handed to me. I'd thank the hospital worker, an elderly man, and sip the hot beverage.

Soon Daniel would be called and taken into the small room for his treatment. Ben, usually content with a toy, and I'd wait in the lobby where I'd pray for all to go well. I also spent time thinking about buying winter clothes for Daniel; he'd outgrown all of his pants, and his next chemo treatments. I sometimes gave a little thought to my pregnancy; I was due in May.

While my thoughts during those chilly mornings changed, the coffee never did. Faithfully, each morning, the worker presented me with a cup. His name was Lawrence, although his name tag said Larry.

Daniel did get winter clothes, and a baby sister. But he never saw his sister as he died three months before her birth.

Now on October mornings, I think of that time at the clinic. Thirteen years later, I still remember the cups of coffee. I look back on that woman of thirty-five, pregnant, with a first grader, a toddler, and a cancer patient. I wonder how she coped. I do know that the kindness of a man who was once a stranger, continues to warm her spirit. He must have seen her coming that first day, fumbling with the front door, hair still damp from her hurried shower, and knew he had to help her in any way he could.

You never know how meaningful your acts of concern---even the simple ones---can be to someone. At the time you perform them, and, many years later.

Soon Daniel would be called and taken into the small room for his treatment. Ben, usually content with a toy, and I'd wait in the lobby where I'd pray for all to go well. I also spent time thinking about buying winter clothes for Daniel; he'd outgrown all of his pants, and his next chemo treatments. I sometimes gave a little thought to my pregnancy; I was due in May.

While my thoughts during those chilly mornings changed, the coffee never did. Faithfully, each morning, the worker presented me with a cup. His name was Lawrence, although his name tag said Larry.

Daniel did get winter clothes, and a baby sister. But he never saw his sister as he died three months before her birth.

Now on October mornings, I think of that time at the clinic. Thirteen years later, I still remember the cups of coffee. I look back on that woman of thirty-five, pregnant, with a first grader, a toddler, and a cancer patient. I wonder how she coped. I do know that the kindness of a man who was once a stranger, continues to warm her spirit. He must have seen her coming that first day, fumbling with the front door, hair still damp from her hurried shower, and knew he had to help her in any way he could.

You never know how meaningful your acts of concern---even the simple ones---can be to someone. At the time you perform them, and, many years later.

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

September Reminds Us

When September rolls around, I look like any other haggled parent standing in the checkout with three kids. The shopping cart is filled with packs of pencils, note paper, crayons, markers, and tissues.

"Why do we need to buy tissues for school?" my kindergartener asked last year.

I pictured a whole class of five-year-olds with runny noses and was tempted to reply, "So kids won't use their sleeves." But I chose the logical, "For when your nose is runny."

My neighbor claimed it would be a busy year when she found out I'd have one in kindergarten, one in first grade and one in middle school. But not busy enough, I thought, and again resisted the urge to let her know that I was wondering what my fifth-grader would be needing for school this year.

My fifth-grader, Daniel, never passed fourth grade. Or third, or even first. He didn't get a school supply list. Instead he got a kit from the hospital with syringes and bandages, all highly sterile.

On Memorial Day Weekend, 1996, Daniel was three and diagnosed with neuroblastoma. After eight months of treatments, surgeries, prayers and hope, this bald-headed kid, who acknowledged he was a “Brave Cookie,” was ready to be a cancer survivor. But a staph infection entered his weakened body and we had to kiss him good-bye.

September—now meaning for me, not only back to school, but Childhood Cancer Awareness Month— has rolled around again and as I stand in line with my kids, I know why the supply lists include tissues.

Just the other day while joining other parents and children in the “shopping for school supplies frenzy,” a woman noticed the gold ribbon pinned to my T-shirt. “What’s gold for?” she asked. “I know that pink is for breast cancer.”

“Children,” I said.

Her puzzled look caused me to further explain. “Gold because our children are golden to us.”

I half expected her to show shock or horror, being one of the thousands who refuses to believe that cancer is the number one illness among children. Another person who has no idea that each year one in every 330 kids will be diagnosed with cancer before age 19.

I was ready for her to walk away from me down the aisle. Why should today be any different? Instead, she mouthed the words, “Did a child of yours . . . ?”

“Yes,” I said, avoiding her look as I grabbed a Curious George notebook. “A son who would be ten now. He died.” He loved Curious George; we'd read it ofen in the hospital.

When I did manage to catch her gaze, her eyes showed tears. They were blue, like my son's.

Then this woman—a stranger—touched my arm. “I am so sorry.” She smiled at my other three children. “They are beautiful. I’m sure your son was, too.”

I nodded, wiped my nose, and thanked her.

If you happen to see a mother wearing a gold ribbon on her shirt—the symbol of childhood cancer awareness—don't be afraid. Ask about the ribbon. The opportunity to talk will help with her healing, and might even give you new wisdom. Most likely, the mother will cry. Feel free to hand her a tissue. Although she has done it before, she probably shouldn't be using her sleeve.

(Borrowed from a piece written by Alice J. Wisler in 2002 and dedicated to all mothers who have to kiss their bald-headed kids "good-bye.")

"Why do we need to buy tissues for school?" my kindergartener asked last year.

I pictured a whole class of five-year-olds with runny noses and was tempted to reply, "So kids won't use their sleeves." But I chose the logical, "For when your nose is runny."

My neighbor claimed it would be a busy year when she found out I'd have one in kindergarten, one in first grade and one in middle school. But not busy enough, I thought, and again resisted the urge to let her know that I was wondering what my fifth-grader would be needing for school this year.

My fifth-grader, Daniel, never passed fourth grade. Or third, or even first. He didn't get a school supply list. Instead he got a kit from the hospital with syringes and bandages, all highly sterile.

On Memorial Day Weekend, 1996, Daniel was three and diagnosed with neuroblastoma. After eight months of treatments, surgeries, prayers and hope, this bald-headed kid, who acknowledged he was a “Brave Cookie,” was ready to be a cancer survivor. But a staph infection entered his weakened body and we had to kiss him good-bye.

September—now meaning for me, not only back to school, but Childhood Cancer Awareness Month— has rolled around again and as I stand in line with my kids, I know why the supply lists include tissues.

Just the other day while joining other parents and children in the “shopping for school supplies frenzy,” a woman noticed the gold ribbon pinned to my T-shirt. “What’s gold for?” she asked. “I know that pink is for breast cancer.”

“Children,” I said.

Her puzzled look caused me to further explain. “Gold because our children are golden to us.”

I half expected her to show shock or horror, being one of the thousands who refuses to believe that cancer is the number one illness among children. Another person who has no idea that each year one in every 330 kids will be diagnosed with cancer before age 19.

I was ready for her to walk away from me down the aisle. Why should today be any different? Instead, she mouthed the words, “Did a child of yours . . . ?”

“Yes,” I said, avoiding her look as I grabbed a Curious George notebook. “A son who would be ten now. He died.” He loved Curious George; we'd read it ofen in the hospital.

When I did manage to catch her gaze, her eyes showed tears. They were blue, like my son's.

Then this woman—a stranger—touched my arm. “I am so sorry.” She smiled at my other three children. “They are beautiful. I’m sure your son was, too.”

I nodded, wiped my nose, and thanked her.

If you happen to see a mother wearing a gold ribbon on her shirt—the symbol of childhood cancer awareness—don't be afraid. Ask about the ribbon. The opportunity to talk will help with her healing, and might even give you new wisdom. Most likely, the mother will cry. Feel free to hand her a tissue. Although she has done it before, she probably shouldn't be using her sleeve.

(Borrowed from a piece written by Alice J. Wisler in 2002 and dedicated to all mothers who have to kiss their bald-headed kids "good-bye.")

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)